|

|

Wypróbuj notatnik Colab Wypróbuj notatnik Colab

|

Wyświetl notatnik na GitHubie Wyświetl notatnik na GitHubie

|

Omówienie

Ten samouczek pokazuje, jak używać wektorów dystrybucyjnych z Gemini API do wykrywania potencjalnych wyników odstających w zbiorze danych. Zwizualizujesz podzbiór zbioru danych 20 grup wiadomości za pomocą parametru t-SNE i wykryjesz wyniki odstające poza określonym promieniem centralnego punktu każdego klastra kategorialnego.

Więcej informacji o tym, jak zacząć korzystać z reprezentacji właściwościowych wygenerowanych za pomocą interfejsu Gemini API, znajdziesz w krótkim wprowadzeniu do Pythona.

Wymagania wstępne

Możesz uruchomić to krótkie wprowadzenie w Google Colab.

Aby ukończyć to krótkie wprowadzenie we własnym środowisku programistycznym, upewnij się, że środowisko spełnia te wymagania:

- Python w wersji 3.9 lub nowszej

- Instalacja programu

jupyterw celu uruchomienia notatnika.

Konfiguracja

Najpierw pobierz i zainstaluj bibliotekę Pythona Gemini API.

pip install -U -q google.generativeai

import re

import tqdm

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

import google.generativeai as genai

# Used to securely store your API key

from google.colab import userdata

from sklearn.datasets import fetch_20newsgroups

from sklearn.manifold import TSNE

Pobierz klucz interfejsu API

Aby móc korzystać z Gemini API, musisz najpierw uzyskać klucz API. Jeśli nie masz jeszcze klucza, utwórz go jednym kliknięciem w Google AI Studio.

Uzyskiwanie klucza interfejsu API

W Colab dodaj klucz do menedżera obiektów tajnych w sekcji „🔑” w panelu po lewej stronie. Nazwij go API_KEY.

Po uzyskaniu klucza interfejsu API przekaż go do pakietu SDK. Można to zrobić na dwa sposoby:

- Umieść ten klucz w zmiennej środowiskowej

GOOGLE_API_KEY(pakiet SDK automatycznie go stamtąd pobierze). - Przekaż klucz urządzeniu

genai.configure(api_key=...)

genai.configure(api_key=GOOGLE_API_KEY)

for m in genai.list_models():

if 'embedContent' in m.supported_generation_methods:

print(m.name)

models/embedding-001 models/embedding-001

Przygotowywanie zbioru danych

Zbiór danych tekstowych grup dyskusyjnych z 20 zawiera 18 000 postów na 20 tematów podzielonych na zbiory treningowe i testowe. Podział między zbiorami danych treningowych i testowych jest oparty na wiadomościach opublikowanych przed określoną datą i po niej. W tym samouczku korzystamy z podzbioru treningowego.

newsgroups_train = fetch_20newsgroups(subset='train')

# View list of class names for dataset

newsgroups_train.target_names

['alt.atheism', 'comp.graphics', 'comp.os.ms-windows.misc', 'comp.sys.ibm.pc.hardware', 'comp.sys.mac.hardware', 'comp.windows.x', 'misc.forsale', 'rec.autos', 'rec.motorcycles', 'rec.sport.baseball', 'rec.sport.hockey', 'sci.crypt', 'sci.electronics', 'sci.med', 'sci.space', 'soc.religion.christian', 'talk.politics.guns', 'talk.politics.mideast', 'talk.politics.misc', 'talk.religion.misc']

Oto pierwszy przykład w zbiorze treningowym.

idx = newsgroups_train.data[0].index('Lines')

print(newsgroups_train.data[0][idx:])

Lines: 15 I was wondering if anyone out there could enlighten me on this car I saw the other day. It was a 2-door sports car, looked to be from the late 60s/ early 70s. It was called a Bricklin. The doors were really small. In addition, the front bumper was separate from the rest of the body. This is all I know. If anyone can tellme a model name, engine specs, years of production, where this car is made, history, or whatever info you have on this funky looking car, please e-mail. Thanks, - IL ---- brought to you by your neighborhood Lerxst ----

# Apply functions to remove names, emails, and extraneous words from data points in newsgroups.data

newsgroups_train.data = [re.sub(r'[\w\.-]+@[\w\.-]+', '', d) for d in newsgroups_train.data] # Remove email

newsgroups_train.data = [re.sub(r"\([^()]*\)", "", d) for d in newsgroups_train.data] # Remove names

newsgroups_train.data = [d.replace("From: ", "") for d in newsgroups_train.data] # Remove "From: "

newsgroups_train.data = [d.replace("\nSubject: ", "") for d in newsgroups_train.data] # Remove "\nSubject: "

# Cut off each text entry after 5,000 characters

newsgroups_train.data = [d[0:5000] if len(d) > 5000 else d for d in newsgroups_train.data]

# Put training points into a dataframe

df_train = pd.DataFrame(newsgroups_train.data, columns=['Text'])

df_train['Label'] = newsgroups_train.target

# Match label to target name index

df_train['Class Name'] = df_train['Label'].map(newsgroups_train.target_names.__getitem__)

df_train

Następnie próbkować część danych, wybierając 150 punktów danych w zbiorze danych treningowych i wybierając kilka kategorii. W tym samouczku używamy kategorii związanych z nauką.

# Take a sample of each label category from df_train

SAMPLE_SIZE = 150

df_train = (df_train.groupby('Label', as_index = False)

.apply(lambda x: x.sample(SAMPLE_SIZE))

.reset_index(drop=True))

# Choose categories about science

df_train = df_train[df_train['Class Name'].str.contains('sci')]

# Reset the index

df_train = df_train.reset_index()

df_train

df_train['Class Name'].value_counts()

sci.crypt 150 sci.electronics 150 sci.med 150 sci.space 150 Name: Class Name, dtype: int64

Tworzenie wektorów dystrybucyjnych

W tej sekcji dowiesz się, jak generować wektory dystrybucyjne dla różnych tekstów w ramce DataFrame przy użyciu wektorów dystrybucyjnych z interfejsu Gemini API.

Zmiany w interfejsie API dotyczące reprezentacji właściwościowych z osadzeniem modelu 001

W nowym modelu wektorów dystrybucyjnych – wektora dystrybucyjnego 001 dostępny jest nowy parametr typu zadania i opcjonalny tytuł (tylko w przypadku parametru event_type=RETRIEVAL_DOCUMENT).

Te nowe parametry mają zastosowanie tylko do najnowszych modeli wektorów dystrybucyjnych.Typy zadań to:

| Typ zadania | Opis |

|---|---|

| RETRIEVAL_QUERY | Określa, że dany tekst jest zapytaniem w ustawieniach wyszukiwania/pobierania. |

| RETRIEVAL_DOCUMENT | Określa, że dany tekst jest dokumentem w ustawieniu wyszukiwania/pobierania. |

| SEMANTIC_SIMILARITY | Określa, który tekst będzie używany na potrzeby funkcji podobieństwo semantycznego (STS). |

| KLASYFIKACJA | Określa, że wektory dystrybucyjne będą używane do klasyfikacji. |

| KLASTEROWANIE | Określa, że wektory dystrybucyjne będą używane do grupowania. |

from tqdm.auto import tqdm

tqdm.pandas()

from google.api_core import retry

def make_embed_text_fn(model):

@retry.Retry(timeout=300.0)

def embed_fn(text: str) -> list[float]:

# Set the task_type to CLUSTERING.

embedding = genai.embed_content(model=model,

content=text,

task_type="clustering")['embedding']

return np.array(embedding)

return embed_fn

def create_embeddings(df):

model = 'models/embedding-001'

df['Embeddings'] = df['Text'].progress_apply(make_embed_text_fn(model))

return df

df_train = create_embeddings(df_train)

df_train.drop('index', axis=1, inplace=True)

0%| | 0/600 [00:00<?, ?it/s]

Redukcja wymiarów

Wymiar wektora dystrybucyjnego dokumentu to 768. Aby wizualizować grupy umieszczonych dokumentów, trzeba zastosować redukcję wymiarów, ponieważ wektory dystrybucyjne można wizualizować tylko w przestrzeni 2D lub 3D. Dokumenty podobne pod względem kontekstu powinny znajdować się bliżej w przestrzeni, w odróżnieniu od dokumentów, które nie są do siebie zbyt podobne.

len(df_train['Embeddings'][0])

768

# Convert df_train['Embeddings'] Pandas series to a np.array of float32

X = np.array(df_train['Embeddings'].to_list(), dtype=np.float32)

X.shape

(600, 768)

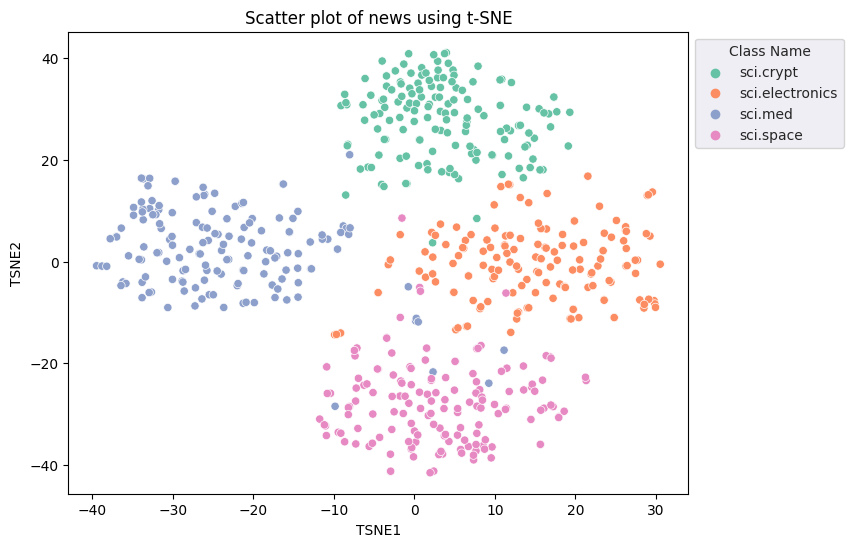

Aby przeprowadzić redukcję wymiarów, zastosujesz metodę t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE). Ta metoda zmniejsza liczbę wymiarów, jednocześnie zachowując klastry (punkty znajdujące się blisko siebie pozostają blisko siebie). W przypadku danych oryginalnych model próbuje utworzyć rozkład, według którego inne punkty danych są „sąsiadami” (na przykład mają podobne znaczenie). Następnie optymalizuje funkcję celu, aby zachować podobny rozkład na wizualizacji.

tsne = TSNE(random_state=0, n_iter=1000)

tsne_results = tsne.fit_transform(X)

df_tsne = pd.DataFrame(tsne_results, columns=['TSNE1', 'TSNE2'])

df_tsne['Class Name'] = df_train['Class Name'] # Add labels column from df_train to df_tsne

df_tsne

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8,6)) # Set figsize

sns.set_style('darkgrid', {"grid.color": ".6", "grid.linestyle": ":"})

sns.scatterplot(data=df_tsne, x='TSNE1', y='TSNE2', hue='Class Name', palette='Set2')

sns.move_legend(ax, "upper left", bbox_to_anchor=(1, 1))

plt.title('Scatter plot of news using t-SNE')

plt.xlabel('TSNE1')

plt.ylabel('TSNE2');

Wykrywanie wyników odstających

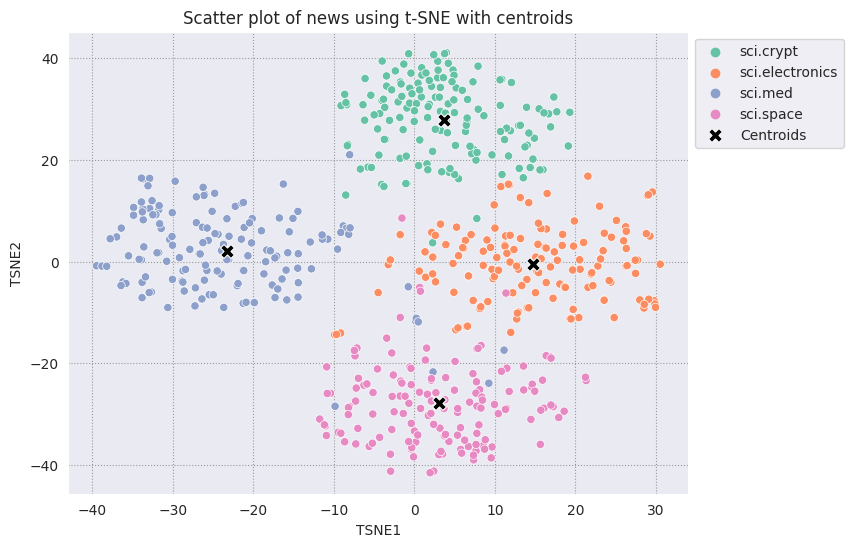

Aby określić, które punkty są nietypowe, musisz określić, które punkty są wskaźnikami intymnymi, a które odstającymi. Zacznij od znalezienia punktu centralnego lub lokalizacji reprezentującej środek gromady, a następnie na podstawie odległości określ punkty, które są odstające od reszty.

Zacznij od wyznaczenia wartości centralnej każdej kategorii.

def get_centroids(df_tsne):

# Get the centroid of each cluster

centroids = df_tsne.groupby('Class Name').mean()

return centroids

centroids = get_centroids(df_tsne)

centroids

def get_embedding_centroids(df):

emb_centroids = dict()

grouped = df.groupby('Class Name')

for c in grouped.groups:

sub_df = grouped.get_group(c)

# Get the centroid value of dimension 768

emb_centroids[c] = np.mean(sub_df['Embeddings'], axis=0)

return emb_centroids

emb_c = get_embedding_centroids(df_train)

Porównaj znaleziony centroid z pozostałymi punktami.

# Plot the centroids against the cluster

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8,6)) # Set figsize

sns.set_style('darkgrid', {"grid.color": ".6", "grid.linestyle": ":"})

sns.scatterplot(data=df_tsne, x='TSNE1', y='TSNE2', hue='Class Name', palette='Set2');

sns.scatterplot(data=centroids, x='TSNE1', y='TSNE2', color="black", marker='X', s=100, label='Centroids')

sns.move_legend(ax, "upper left", bbox_to_anchor=(1, 1))

plt.title('Scatter plot of news using t-SNE with centroids')

plt.xlabel('TSNE1')

plt.ylabel('TSNE2');

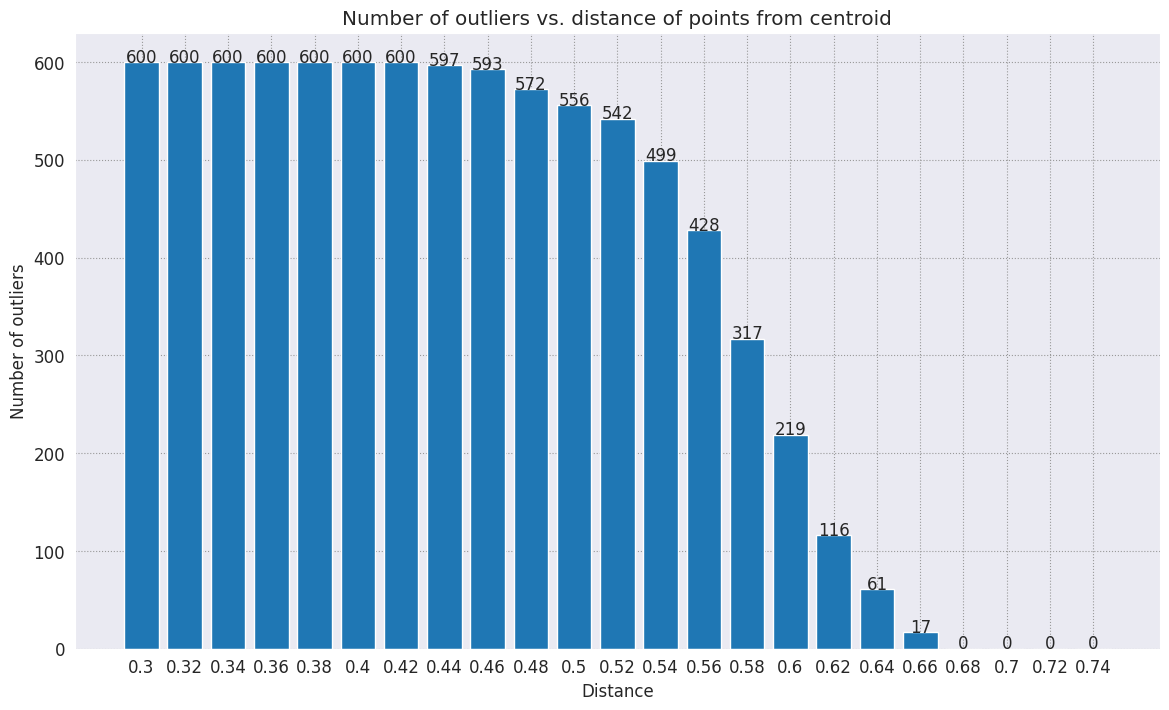

Wybierz promień. Wszystko, co wykracza poza tę granicę, jest uznawane za wartości odstające.

def calculate_euclidean_distance(p1, p2):

return np.sqrt(np.sum(np.square(p1 - p2)))

def detect_outlier(df, emb_centroids, radius):

for idx, row in df.iterrows():

class_name = row['Class Name'] # Get class name of row

# Compare centroid distances

dist = calculate_euclidean_distance(row['Embeddings'],

emb_centroids[class_name])

df.at[idx, 'Outlier'] = dist > radius

return len(df[df['Outlier'] == True])

range_ = np.arange(0.3, 0.75, 0.02).round(decimals=2).tolist()

num_outliers = []

for i in range_:

num_outliers.append(detect_outlier(df_train, emb_c, i))

# Plot range_ and num_outliers

fig = plt.figure(figsize = (14, 8))

plt.rcParams.update({'font.size': 12})

plt.bar(list(map(str, range_)), num_outliers)

plt.title("Number of outliers vs. distance of points from centroid")

plt.xlabel("Distance")

plt.ylabel("Number of outliers")

for i in range(len(range_)):

plt.text(i, num_outliers[i], num_outliers[i], ha = 'center')

plt.show()

W zależności od tego, jak czuły ma być wykrywacz anomalii, możesz wybrać promień, którego chcesz użyć. Na razie używana jest wartość 0, 62, ale możesz ją zmienić.

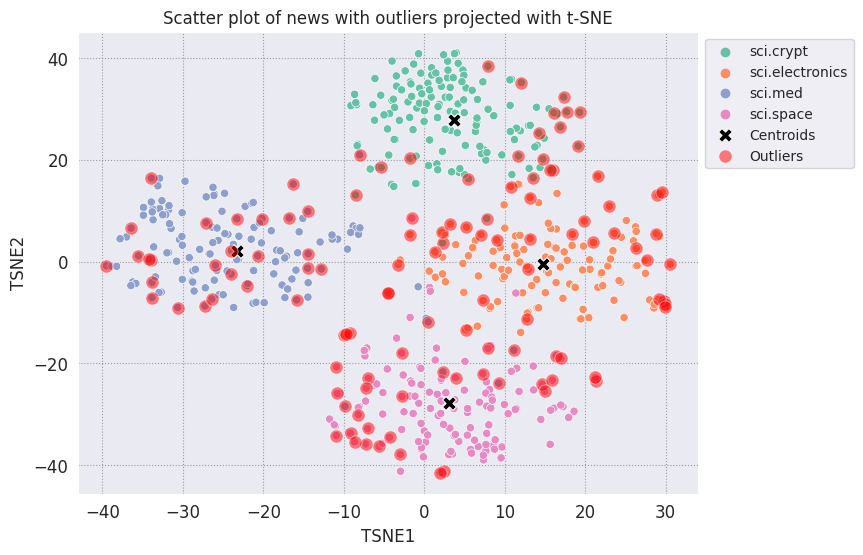

# View the points that are outliers

RADIUS = 0.62

detect_outlier(df_train, emb_c, RADIUS)

df_outliers = df_train[df_train['Outlier'] == True]

df_outliers.head()

# Use the index to map the outlier points back to the projected TSNE points

outliers_projected = df_tsne.loc[df_outliers['Outlier'].index]

Zaznacz odchylenia od normy i oznacz je za pomocą przezroczystego czerwonego koloru.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8,6)) # Set figsize

plt.rcParams.update({'font.size': 10})

sns.set_style('darkgrid', {"grid.color": ".6", "grid.linestyle": ":"})

sns.scatterplot(data=df_tsne, x='TSNE1', y='TSNE2', hue='Class Name', palette='Set2');

sns.scatterplot(data=centroids, x='TSNE1', y='TSNE2', color="black", marker='X', s=100, label='Centroids')

# Draw a red circle around the outliers

sns.scatterplot(data=outliers_projected, x='TSNE1', y='TSNE2', color='red', marker='o', alpha=0.5, s=90, label='Outliers')

sns.move_legend(ax, "upper left", bbox_to_anchor=(1, 1))

plt.title('Scatter plot of news with outliers projected with t-SNE')

plt.xlabel('TSNE1')

plt.ylabel('TSNE2');

Użyj wartości indeksów datafames, aby wyświetlić kilka przykładów wyników odstających w każdej kategorii. Tutaj wyświetlany jest pierwszy punkt danych z każdej kategorii. Przejrzyj inne punkty w każdej kategorii, aby zobaczyć dane, które są uznawane za dane odstające lub anomalie.

sci_crypt_outliers = df_outliers[df_outliers['Class Name'] == 'sci.crypt']

print(sci_crypt_outliers['Text'].iloc[0])

Re: Source of random bits on a Unix workstation Lines: 44 Nntp-Posting-Host: sandstorm >>For your application, what you can do is to encrypt the real-time clock >>value with a secret key. Well, almost.... If I only had to solve the problem for myself, and were willing to have to type in a second password whenever I logged in, it could work. However, I'm trying to create a solution that anyone can use, and which, once installed, is just as effortless to start up as the non-solution of just using xhost to control access. I've got religeous problems with storing secret keys on multiuser computers. >For a good discussion of cryptographically "good" random number >generators, check out the draft-ietf-security-randomness-00.txt >Internet Draft, available at your local friendly internet drafts >repository. Thanks for the pointer! It was good reading, and I liked the idea of using several unrelated sources with a strong mixing function. However, unless I missed something, the only source they suggested that seems available, and unguessable by an intruder, when a Unix is fresh-booted, is I/O buffers related to network traffic. I believe my solution basically uses that strategy, without requiring me to reach into the kernel. >A reasonably source of randomness is the output of a cryptographic >hash function , when fed with a large amount of >more-or-less random data. For example, running MD5 on /dev/mem is a >slow, but random enough, source of random bits; there are bound to be >128 bits of entropy in the tens of megabytes of data in >a modern workstation's memory, as a fair amount of them are system >timers, i/o buffers, etc. I heard about this solution, and it sounded good. Then I heard that folks were experiencing times of 30-60 seconds to run this, on reasonably-configured workstations. I'm not willing to add that much delay to someone's login process. My approach takes a second or two to run. I'm considering writing the be-all and end-all of solutions, that launches the MD5, and simultaneously tries to suck bits off the net, and if the net should be sitting __SO__ idle that it can't get 10K after compression before MD5 finishes, use the MD5. This way I could have guaranteed good bits, and a deterministic upper bound on login time, and still have the common case of login take only a couple of extra seconds. -Bennett

sci_elec_outliers = df_outliers[df_outliers['Class Name'] == 'sci.electronics']

print(sci_elec_outliers['Text'].iloc[0])

Re: Laser vs Bubblejet?

Reply-To:

Distribution: world

X-Mailer: cppnews \\(Revision: 1.20 \\)

Organization: null

Lines: 53

Here is a different viewpoint.

> FYI: The actual horizontal dot placement resoution of an HP

> deskjet is 1/600th inch. The electronics and dynamics of the ink

> cartridge, however, limit you to generating dots at 300 per inch.

> On almost any paper, the ink wicks more than 1/300th inch anyway.

>

> The method of depositing and fusing toner of a laster printer

> results in much less spread than ink drop technology.

In practice there is little difference in quality but more care is needed

with inkjet because smudges etc. can happen.

> It doesn't take much investigation to see that the mechanical and

> electronic complement of a laser printer is more complex than

> inexpensive ink jet printers. Recall also that laser printers

> offer a much higher throughput: 10 ppm for a laser versus about 1

> ppm for an ink jet printer.

A cheap laser printer does not manage that sort of throughput and on top of

that how long does the _first_ sheet take to print? Inkjets are faster than

you say and in both cases the computer often has trouble keeping up with the

printer.

A sage said to me: "Do you want one copy or lots of copies?", "One",

"Inkjet".

> Something else to think about is the cost of consumables over the

> life of the printer. A 3000 page yield toner cartridge is about

> $US 75-80 at discount while HP high capacity

> cartridges are about $US 22 at discount. It could be that over the

> life cycle of the printer that consumables for laser printers are

> less than ink jet printers. It is getting progressively closer

> between the two technologies. Laser printers are usually desinged

> for higher duty cycles in pages per month and longer product

> replacement cycles.

Paper cost is the same and both can use refills. Long term the laserprinter

will need some expensive replacement parts and on top of that

are the amortisation costs which favour the lowest purchase cost printer.

HP inkjets understand PCL so in many cases a laserjet driver will work if the

software package has no inkjet driver.

There is one wild difference between the two printers: a laserprinter is a

page printer whilst an inkjet is a line printer. This means that a

laserprinter can rotate graphic images whilst an inkjet cannot. Few drivers

actually use this facility.

TC.

E-mail: or

sci_med_outliers = df_outliers[df_outliers['Class Name'] == 'sci.med']

print(sci_med_outliers['Text'].iloc[0])

Re: THE BACK MACHINE - Update Organization: University of Nebraska--Lincoln Lines: 15 Distribution: na NNTP-Posting-Host: unlinfo.unl.edu I have a BACK MACHINE and have had one since January. While I have not found it to be a panacea for my back pain, I think it has helped somewhat. It MAINLY acts to stretch muscles in the back and prevent spasms associated with pain. I am taking less pain medication than I was previously. The folks at BACK TECHNOLOGIES are VERY reluctant to honor their return policy. They extended my "warranty" period rather than allow me to return the machine when, after the first month or so, I was not thrilled with it. They encouraged me to continue to use it, abeit less vigourously. Like I said, I can't say it is a cure-all, but it keeps me stretched out and I am in less pain. -- *********************************************************************** Dale M. Webb, DVM, PhD * 97% of the body is water. The Veterinary Diagnostic Center * other 3% keeps you from drowning. University of Nebraska, Lincoln *

sci_space_outliers = df_outliers[df_outliers['Class Name'] == 'sci.space']

print(sci_space_outliers['Text'].iloc[0])

MACH 25 landing site bases? Article-I.D.: aurora.1993Apr5.193829.1 Organization: University of Alaska Fairbanks Lines: 7 Nntp-Posting-Host: acad3.alaska.edu The supersonic booms hear a few months ago over I belive San Fran, heading east of what I heard, some new super speed Mach 25 aircraft?? What military based int he direction of flight are there that could handle a Mach 25aircraft on its landing decent?? Odd question?? == Michael Adams, -- I'm not high, just jacked

Dalsze kroki

Udało Ci się utworzyć detektor anomalii z użyciem wektorów dystrybucyjnych. Spróbuj użyć własnych danych tekstowych, aby zwizualizować je jako wektory dystrybucyjne i wybrać pewne granice, aby móc wykrywać wyniki odstające. Aby ukończyć etap wizualizacji, możesz przeprowadzić redukcję wymiarów. Pamiętaj, że t-SNE dobrze nadaje się do grupowania danych wejściowych, ale uzgadnianie procesu może trwać dłużej lub może utknąć na poziomie lokalnego minima. Jeśli natrafisz na ten problem, możesz też rozważyć analizę komponentów głównych (PCA).

Więcej informacji na temat korzystania z wektorów dystrybucyjnych można znaleźć w innych samouczkach: