|

|

Prueba un notebook de Colab Prueba un notebook de Colab

|

Ver notebook en GitHub Ver notebook en GitHub

|

Descripción general

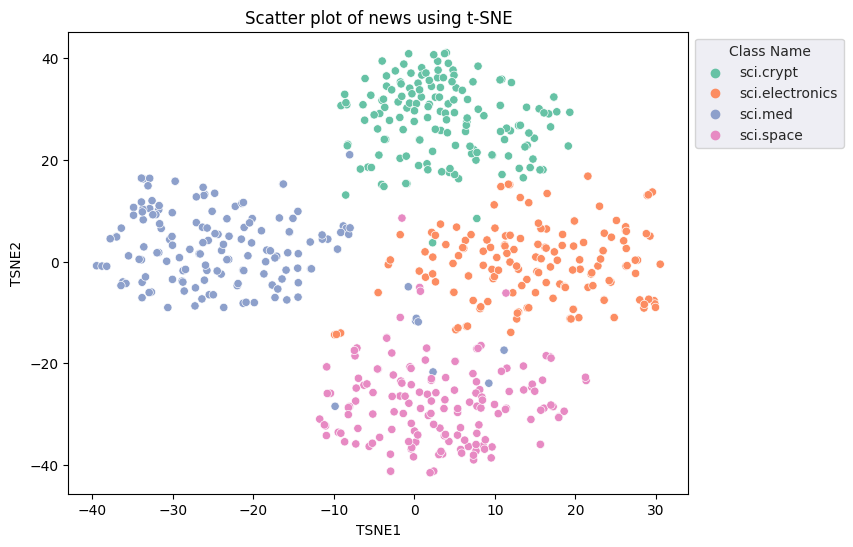

En este instructivo, se muestra cómo usar las incorporaciones de la API de Gemini para detectar posibles valores atípicos en tu conjunto de datos. Visualizarás un subconjunto de los 20 conjuntos de datos de Newsgroup mediante t-SNE y detectarás valores atípicos fuera de un radio particular del punto central de cada grupo categórico.

Si quieres obtener más información para comenzar a usar las incorporaciones generadas a partir de la API de Gemini, consulta la guía de inicio rápido de Python.

Requisitos previos

Puedes ejecutar esta guía de inicio rápido en Google Colab.

Para completar esta guía de inicio rápido en tu entorno de desarrollo, asegúrate de que tu entorno cumpla con los siguientes requisitos:

- Python 3.9 y versiones posteriores

- Una instalación de

jupyterpara ejecutar el notebook

Configuración

Primero, descarga e instala la biblioteca de Python de la API de Gemini.

pip install -U -q google.generativeai

import re

import tqdm

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

import google.generativeai as genai

# Used to securely store your API key

from google.colab import userdata

from sklearn.datasets import fetch_20newsgroups

from sklearn.manifold import TSNE

Obtén una clave de API

Para poder usar la API de Gemini, primero debes obtener una clave de API. Si aún no tienes una, crea una clave con un clic en Google AI Studio.

En Colab, agrega la clave al administrador de Secrets en la "Notebook" que aparece a continuación. en el panel izquierdo. Asígnale el nombre API_KEY.

Una vez que tengas la clave de API, pásala al SDK. Puedes hacerlo de dos maneras:

- Coloca la clave en la variable de entorno

GOOGLE_API_KEY(el SDK la recogerá automáticamente desde allí). - Pasa la clave a

genai.configure(api_key=...)

genai.configure(api_key=GOOGLE_API_KEY)

for m in genai.list_models():

if 'embedContent' in m.supported_generation_methods:

print(m.name)

models/embedding-001 models/embedding-001

Preparar conjunto de datos

El conjunto de datos de texto de 20 grupos de noticias contiene 18,000 publicaciones de grupos de noticias sobre 20 temas divididos en conjuntos de capacitación y prueba. La división entre los conjuntos de datos de entrenamiento y prueba se basa en los mensajes publicados antes y después de una fecha específica. En este instructivo, se usa el subconjunto de entrenamiento.

newsgroups_train = fetch_20newsgroups(subset='train')

# View list of class names for dataset

newsgroups_train.target_names

['alt.atheism', 'comp.graphics', 'comp.os.ms-windows.misc', 'comp.sys.ibm.pc.hardware', 'comp.sys.mac.hardware', 'comp.windows.x', 'misc.forsale', 'rec.autos', 'rec.motorcycles', 'rec.sport.baseball', 'rec.sport.hockey', 'sci.crypt', 'sci.electronics', 'sci.med', 'sci.space', 'soc.religion.christian', 'talk.politics.guns', 'talk.politics.mideast', 'talk.politics.misc', 'talk.religion.misc']

Este es el primer ejemplo del conjunto de entrenamiento.

idx = newsgroups_train.data[0].index('Lines')

print(newsgroups_train.data[0][idx:])

Lines: 15 I was wondering if anyone out there could enlighten me on this car I saw the other day. It was a 2-door sports car, looked to be from the late 60s/ early 70s. It was called a Bricklin. The doors were really small. In addition, the front bumper was separate from the rest of the body. This is all I know. If anyone can tellme a model name, engine specs, years of production, where this car is made, history, or whatever info you have on this funky looking car, please e-mail. Thanks, - IL ---- brought to you by your neighborhood Lerxst ----

# Apply functions to remove names, emails, and extraneous words from data points in newsgroups.data

newsgroups_train.data = [re.sub(r'[\w\.-]+@[\w\.-]+', '', d) for d in newsgroups_train.data] # Remove email

newsgroups_train.data = [re.sub(r"\([^()]*\)", "", d) for d in newsgroups_train.data] # Remove names

newsgroups_train.data = [d.replace("From: ", "") for d in newsgroups_train.data] # Remove "From: "

newsgroups_train.data = [d.replace("\nSubject: ", "") for d in newsgroups_train.data] # Remove "\nSubject: "

# Cut off each text entry after 5,000 characters

newsgroups_train.data = [d[0:5000] if len(d) > 5000 else d for d in newsgroups_train.data]

# Put training points into a dataframe

df_train = pd.DataFrame(newsgroups_train.data, columns=['Text'])

df_train['Label'] = newsgroups_train.target

# Match label to target name index

df_train['Class Name'] = df_train['Label'].map(newsgroups_train.target_names.__getitem__)

df_train

A continuación, toma muestras de algunos de los datos. Para ello, toma 150 datos en el conjunto de datos de entrenamiento y elige algunas categorías. En este instructivo, se usan las categorías de ciencia.

# Take a sample of each label category from df_train

SAMPLE_SIZE = 150

df_train = (df_train.groupby('Label', as_index = False)

.apply(lambda x: x.sample(SAMPLE_SIZE))

.reset_index(drop=True))

# Choose categories about science

df_train = df_train[df_train['Class Name'].str.contains('sci')]

# Reset the index

df_train = df_train.reset_index()

df_train

df_train['Class Name'].value_counts()

sci.crypt 150 sci.electronics 150 sci.med 150 sci.space 150 Name: Class Name, dtype: int64

Crea las incorporaciones

En esta sección, verás cómo generar incorporaciones para los diferentes textos en el marco de datos usando las incorporaciones de la API de Gemini.

Cambios en la API a las incorporaciones con el modelo embedding-001

Para el nuevo modelo de incorporaciones, embedding-001, hay un nuevo parámetro de tipo de tarea y el título opcional (solo válido con task_type=RETRIEVAL_DOCUMENT).

Estos parámetros nuevos se aplican solo a los modelos de incorporaciones más recientes.Los tipos de tareas son los siguientes:

| Tipo de tarea | Descripción |

|---|---|

| RETRIEVAL_QUERY | Especifica que el texto dado es una consulta en un parámetro de configuración de búsqueda/recuperación. |

| RETRIEVAL_DOCUMENT | Especifica que el texto dado de un documento en un parámetro de configuración de búsqueda y recuperación. |

| SEMANTIC_SIMILARITY | Especifica que el texto dado se usará para la similitud textual semántica (STS). |

| CLASIFICACIÓN | Especifica que las incorporaciones se usarán para la clasificación. |

| Agrupamiento en clústeres | Especifica que las incorporaciones se usarán para el agrupamiento en clústeres. |

from tqdm.auto import tqdm

tqdm.pandas()

from google.api_core import retry

def make_embed_text_fn(model):

@retry.Retry(timeout=300.0)

def embed_fn(text: str) -> list[float]:

# Set the task_type to CLUSTERING.

embedding = genai.embed_content(model=model,

content=text,

task_type="clustering")['embedding']

return np.array(embedding)

return embed_fn

def create_embeddings(df):

model = 'models/embedding-001'

df['Embeddings'] = df['Text'].progress_apply(make_embed_text_fn(model))

return df

df_train = create_embeddings(df_train)

df_train.drop('index', axis=1, inplace=True)

0%| | 0/600 [00:00<?, ?it/s]

Reducción de la dimensionalidad

La dimensión del vector de incorporación de documentos es 768. Para visualizar cómo se agrupan los documentos incorporados, deberás aplicar la reducción de dimensionalidad, ya que solo puedes visualizar las incorporaciones en un espacio 2D o 3D. Los documentos contextualmente similares deben estar más juntos en el espacio a diferencia de los documentos que no son tan similares.

len(df_train['Embeddings'][0])

768

# Convert df_train['Embeddings'] Pandas series to a np.array of float32

X = np.array(df_train['Embeddings'].to_list(), dtype=np.float32)

X.shape

(600, 768)

Aplicarás el enfoque de incorporación estocástica de vecinos estocástico distribuida (t-SNE) para realizar una reducción de la dimensionalidad. Esta técnica reduce la cantidad de dimensiones y, al mismo tiempo, preserva los clústeres (los puntos que están juntos permanecen cerca). Para los datos originales, el modelo intenta construir una distribución sobre la cual otros datos son "vecinos" (p.ej., comparten un significado similar). Luego, optimiza una función objetiva para mantener una distribución similar en la visualización.

tsne = TSNE(random_state=0, n_iter=1000)

tsne_results = tsne.fit_transform(X)

df_tsne = pd.DataFrame(tsne_results, columns=['TSNE1', 'TSNE2'])

df_tsne['Class Name'] = df_train['Class Name'] # Add labels column from df_train to df_tsne

df_tsne

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8,6)) # Set figsize

sns.set_style('darkgrid', {"grid.color": ".6", "grid.linestyle": ":"})

sns.scatterplot(data=df_tsne, x='TSNE1', y='TSNE2', hue='Class Name', palette='Set2')

sns.move_legend(ax, "upper left", bbox_to_anchor=(1, 1))

plt.title('Scatter plot of news using t-SNE')

plt.xlabel('TSNE1')

plt.ylabel('TSNE2');

Detección de valores atípicos

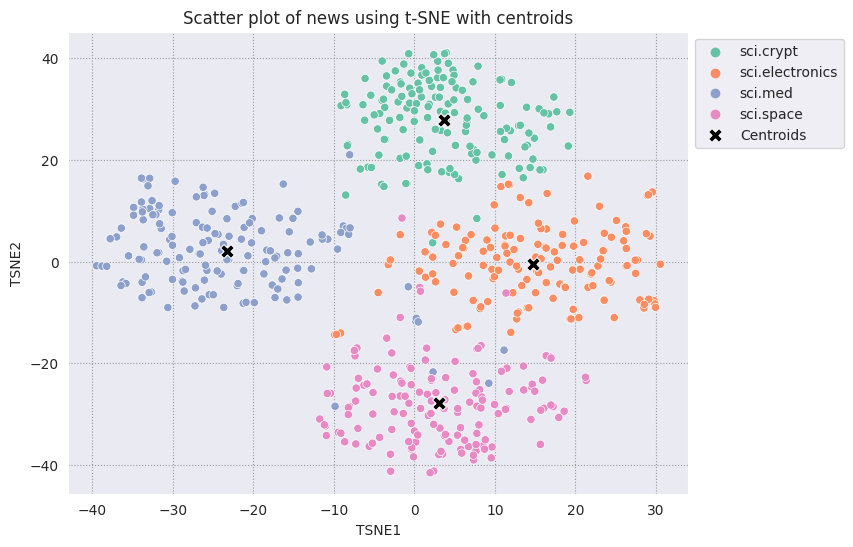

Para determinar qué puntos son anómalos, determinarás cuáles son valores atípicos y atípicos. Comienza buscando el centroide, o la ubicación que representa el centro del clúster, y usa la distancia para determinar los puntos que son valores atípicos.

Comienza por obtener el centroide de cada categoría.

def get_centroids(df_tsne):

# Get the centroid of each cluster

centroids = df_tsne.groupby('Class Name').mean()

return centroids

centroids = get_centroids(df_tsne)

centroids

def get_embedding_centroids(df):

emb_centroids = dict()

grouped = df.groupby('Class Name')

for c in grouped.groups:

sub_df = grouped.get_group(c)

# Get the centroid value of dimension 768

emb_centroids[c] = np.mean(sub_df['Embeddings'], axis=0)

return emb_centroids

emb_c = get_embedding_centroids(df_train)

Traza cada centroide que hayas encontrado en comparación con el resto de los puntos.

# Plot the centroids against the cluster

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8,6)) # Set figsize

sns.set_style('darkgrid', {"grid.color": ".6", "grid.linestyle": ":"})

sns.scatterplot(data=df_tsne, x='TSNE1', y='TSNE2', hue='Class Name', palette='Set2');

sns.scatterplot(data=centroids, x='TSNE1', y='TSNE2', color="black", marker='X', s=100, label='Centroids')

sns.move_legend(ax, "upper left", bbox_to_anchor=(1, 1))

plt.title('Scatter plot of news using t-SNE with centroids')

plt.xlabel('TSNE1')

plt.ylabel('TSNE2');

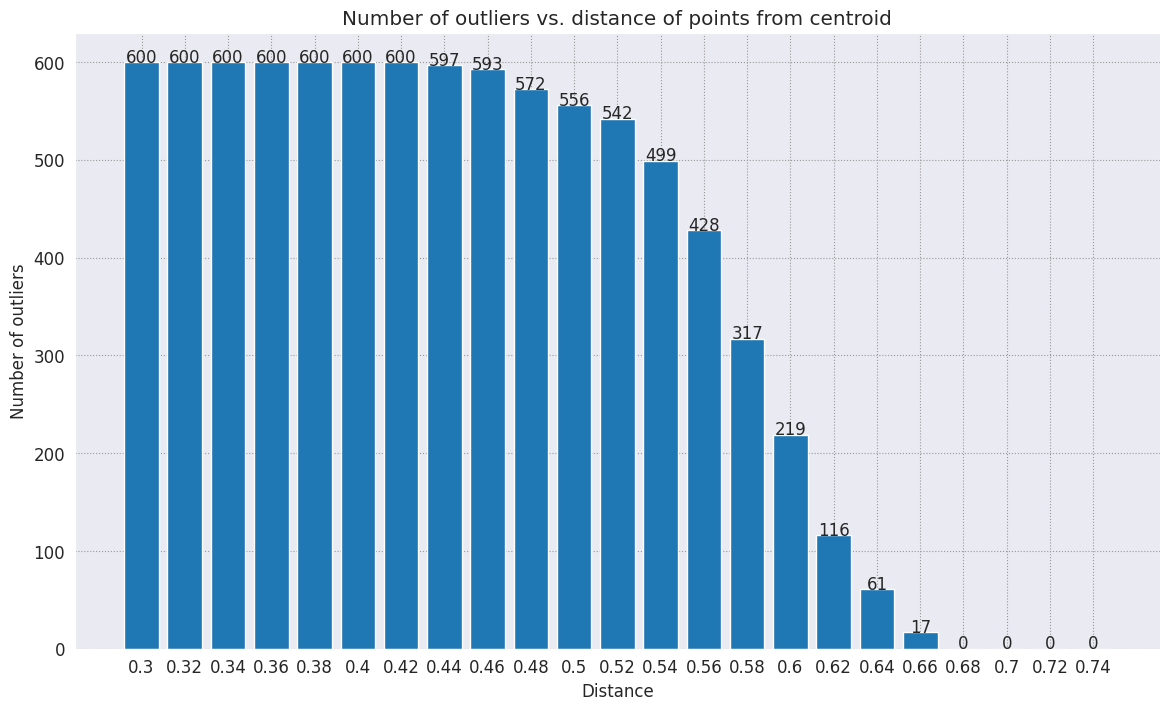

Elige un radio. Todo lo que se encuentre fuera de este límite desde el centroide de esa categoría se considera un valor atípico.

def calculate_euclidean_distance(p1, p2):

return np.sqrt(np.sum(np.square(p1 - p2)))

def detect_outlier(df, emb_centroids, radius):

for idx, row in df.iterrows():

class_name = row['Class Name'] # Get class name of row

# Compare centroid distances

dist = calculate_euclidean_distance(row['Embeddings'],

emb_centroids[class_name])

df.at[idx, 'Outlier'] = dist > radius

return len(df[df['Outlier'] == True])

range_ = np.arange(0.3, 0.75, 0.02).round(decimals=2).tolist()

num_outliers = []

for i in range_:

num_outliers.append(detect_outlier(df_train, emb_c, i))

# Plot range_ and num_outliers

fig = plt.figure(figsize = (14, 8))

plt.rcParams.update({'font.size': 12})

plt.bar(list(map(str, range_)), num_outliers)

plt.title("Number of outliers vs. distance of points from centroid")

plt.xlabel("Distance")

plt.ylabel("Number of outliers")

for i in range(len(range_)):

plt.text(i, num_outliers[i], num_outliers[i], ha = 'center')

plt.show()

Según la sensibilidad que desees que tenga el detector de anomalías, puedes elegir el radio que deseas utilizar. Por ahora, se usa 0.62, pero puedes cambiar este valor.

# View the points that are outliers

RADIUS = 0.62

detect_outlier(df_train, emb_c, RADIUS)

df_outliers = df_train[df_train['Outlier'] == True]

df_outliers.head()

# Use the index to map the outlier points back to the projected TSNE points

outliers_projected = df_tsne.loc[df_outliers['Outlier'].index]

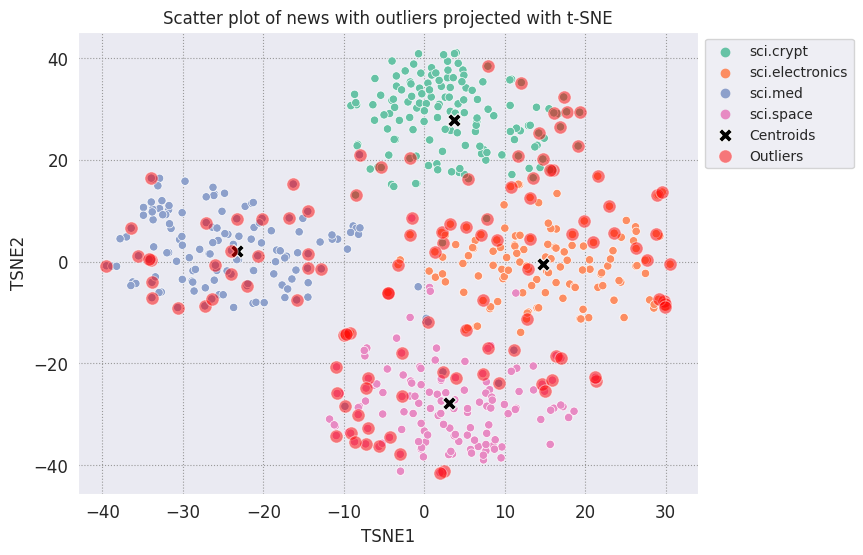

Traza los valores atípicos y denotalos con un color rojo transparente.

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8,6)) # Set figsize

plt.rcParams.update({'font.size': 10})

sns.set_style('darkgrid', {"grid.color": ".6", "grid.linestyle": ":"})

sns.scatterplot(data=df_tsne, x='TSNE1', y='TSNE2', hue='Class Name', palette='Set2');

sns.scatterplot(data=centroids, x='TSNE1', y='TSNE2', color="black", marker='X', s=100, label='Centroids')

# Draw a red circle around the outliers

sns.scatterplot(data=outliers_projected, x='TSNE1', y='TSNE2', color='red', marker='o', alpha=0.5, s=90, label='Outliers')

sns.move_legend(ax, "upper left", bbox_to_anchor=(1, 1))

plt.title('Scatter plot of news with outliers projected with t-SNE')

plt.xlabel('TSNE1')

plt.ylabel('TSNE2');

Usa los valores de índice de las familias de datos para imprimir algunos ejemplos de cómo pueden verse los valores atípicos en cada categoría. Aquí, se imprime el primer dato de cada categoría. Explora otros puntos de cada categoría para ver los datos que se consideran valores atípicos o anomalías.

sci_crypt_outliers = df_outliers[df_outliers['Class Name'] == 'sci.crypt']

print(sci_crypt_outliers['Text'].iloc[0])

Re: Source of random bits on a Unix workstation Lines: 44 Nntp-Posting-Host: sandstorm >>For your application, what you can do is to encrypt the real-time clock >>value with a secret key. Well, almost.... If I only had to solve the problem for myself, and were willing to have to type in a second password whenever I logged in, it could work. However, I'm trying to create a solution that anyone can use, and which, once installed, is just as effortless to start up as the non-solution of just using xhost to control access. I've got religeous problems with storing secret keys on multiuser computers. >For a good discussion of cryptographically "good" random number >generators, check out the draft-ietf-security-randomness-00.txt >Internet Draft, available at your local friendly internet drafts >repository. Thanks for the pointer! It was good reading, and I liked the idea of using several unrelated sources with a strong mixing function. However, unless I missed something, the only source they suggested that seems available, and unguessable by an intruder, when a Unix is fresh-booted, is I/O buffers related to network traffic. I believe my solution basically uses that strategy, without requiring me to reach into the kernel. >A reasonably source of randomness is the output of a cryptographic >hash function , when fed with a large amount of >more-or-less random data. For example, running MD5 on /dev/mem is a >slow, but random enough, source of random bits; there are bound to be >128 bits of entropy in the tens of megabytes of data in >a modern workstation's memory, as a fair amount of them are system >timers, i/o buffers, etc. I heard about this solution, and it sounded good. Then I heard that folks were experiencing times of 30-60 seconds to run this, on reasonably-configured workstations. I'm not willing to add that much delay to someone's login process. My approach takes a second or two to run. I'm considering writing the be-all and end-all of solutions, that launches the MD5, and simultaneously tries to suck bits off the net, and if the net should be sitting __SO__ idle that it can't get 10K after compression before MD5 finishes, use the MD5. This way I could have guaranteed good bits, and a deterministic upper bound on login time, and still have the common case of login take only a couple of extra seconds. -Bennett

sci_elec_outliers = df_outliers[df_outliers['Class Name'] == 'sci.electronics']

print(sci_elec_outliers['Text'].iloc[0])

Re: Laser vs Bubblejet?

Reply-To:

Distribution: world

X-Mailer: cppnews \\(Revision: 1.20 \\)

Organization: null

Lines: 53

Here is a different viewpoint.

> FYI: The actual horizontal dot placement resoution of an HP

> deskjet is 1/600th inch. The electronics and dynamics of the ink

> cartridge, however, limit you to generating dots at 300 per inch.

> On almost any paper, the ink wicks more than 1/300th inch anyway.

>

> The method of depositing and fusing toner of a laster printer

> results in much less spread than ink drop technology.

In practice there is little difference in quality but more care is needed

with inkjet because smudges etc. can happen.

> It doesn't take much investigation to see that the mechanical and

> electronic complement of a laser printer is more complex than

> inexpensive ink jet printers. Recall also that laser printers

> offer a much higher throughput: 10 ppm for a laser versus about 1

> ppm for an ink jet printer.

A cheap laser printer does not manage that sort of throughput and on top of

that how long does the _first_ sheet take to print? Inkjets are faster than

you say and in both cases the computer often has trouble keeping up with the

printer.

A sage said to me: "Do you want one copy or lots of copies?", "One",

"Inkjet".

> Something else to think about is the cost of consumables over the

> life of the printer. A 3000 page yield toner cartridge is about

> $US 75-80 at discount while HP high capacity

> cartridges are about $US 22 at discount. It could be that over the

> life cycle of the printer that consumables for laser printers are

> less than ink jet printers. It is getting progressively closer

> between the two technologies. Laser printers are usually desinged

> for higher duty cycles in pages per month and longer product

> replacement cycles.

Paper cost is the same and both can use refills. Long term the laserprinter

will need some expensive replacement parts and on top of that

are the amortisation costs which favour the lowest purchase cost printer.

HP inkjets understand PCL so in many cases a laserjet driver will work if the

software package has no inkjet driver.

There is one wild difference between the two printers: a laserprinter is a

page printer whilst an inkjet is a line printer. This means that a

laserprinter can rotate graphic images whilst an inkjet cannot. Few drivers

actually use this facility.

TC.

E-mail: or

sci_med_outliers = df_outliers[df_outliers['Class Name'] == 'sci.med']

print(sci_med_outliers['Text'].iloc[0])

Re: THE BACK MACHINE - Update Organization: University of Nebraska--Lincoln Lines: 15 Distribution: na NNTP-Posting-Host: unlinfo.unl.edu I have a BACK MACHINE and have had one since January. While I have not found it to be a panacea for my back pain, I think it has helped somewhat. It MAINLY acts to stretch muscles in the back and prevent spasms associated with pain. I am taking less pain medication than I was previously. The folks at BACK TECHNOLOGIES are VERY reluctant to honor their return policy. They extended my "warranty" period rather than allow me to return the machine when, after the first month or so, I was not thrilled with it. They encouraged me to continue to use it, abeit less vigourously. Like I said, I can't say it is a cure-all, but it keeps me stretched out and I am in less pain. -- *********************************************************************** Dale M. Webb, DVM, PhD * 97% of the body is water. The Veterinary Diagnostic Center * other 3% keeps you from drowning. University of Nebraska, Lincoln *

sci_space_outliers = df_outliers[df_outliers['Class Name'] == 'sci.space']

print(sci_space_outliers['Text'].iloc[0])

MACH 25 landing site bases? Article-I.D.: aurora.1993Apr5.193829.1 Organization: University of Alaska Fairbanks Lines: 7 Nntp-Posting-Host: acad3.alaska.edu The supersonic booms hear a few months ago over I belive San Fran, heading east of what I heard, some new super speed Mach 25 aircraft?? What military based int he direction of flight are there that could handle a Mach 25aircraft on its landing decent?? Odd question?? == Michael Adams, -- I'm not high, just jacked

Próximos pasos

Ya creaste un detector de anomalías con incorporaciones. Intenta usar tus propios datos textuales para visualizarlos como incorporaciones y elige algunos límites de modo que puedas detectar valores atípicos. Puedes realizar una reducción de la dimensionalidad para completar el paso de visualización. Ten en cuenta que t-SNE es bueno para agrupar entradas en clústeres, pero puede tardar más tiempo en converger o puede bloquearse en los mínimos locales. Si te encuentras con este problema, otra técnica que puedes considerar es el análisis de componentes principales (ACP).

Para obtener más información sobre cómo usar las incorporaciones, consulta estos otros instructivos: